Cyclone Center News and Updates

Hello Classifiers and Friends! There have been a number of recent developments in Cyclone Center world in recent weeks. Have a read and then head over to the Cyclone Center website and help us keep the classifying momentum!

New Cyclone Center Journal Article Accepted

CC scientist Dr. Ken Knapp from the U.S. National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) in Asheville, NC is the lead author on a new paper just recently accepted into the journal Monthly Weather Review. Titled “Identification of tropical cyclone ‘storm types’ Read More…

Most Uncertain Storm Images

One of the great things about crowd sourcing is that we have the luxury of using numerous classifications to determine an answer for one image. The responses of 15 citizen scientists is much more powerful than a response from one person, even if that person is an expert.

We have gone through every single storm image on Cyclone Center that has been classified by at least 10 citizen scientists. All classifications were used to determine the variance of the image – or, how similar one classification was to the others. Ambiguous cloud patterns will have a higher variance than one with a clear eye, for example.

Joaquin: Classifying Shear Storms in Cyclone Center

Tropical Storm Joaquin is moving slowly over warm North Atlantic waters this evening. If atmospheric conditions were ideal, Joaquin would be well on his way to becoming a hurricane. Instead, he is struggling to develop because the atmospheric winds are creating strong “shear” which displaces the energy source of the storm away from the center. Watch the animated image below:

A tale of two storms

The mystical nature of tropical cyclones is that they even form at all. They begin as convective cells (what could be called large thunderstorms). What appears to be a disorganized grouping of storm cells, can organize, begin spinning and in no time, appear to be a fully organized system. Of course there are very technical descriptions as to how this occurs, but from satellite imagery, it can be amazing to watch. While some of the larger convective (colder) cells can appear to be a separate system, they often are actually part of the original circulation. Here are a couple examples recently brought up on the talk forum at talk.cyclonecenter.org, both of which had two significant landfalls.

1989 Typhoon Gay

This system was interesting in that it is a system that began in the Gulf of Thailand – considered the Pacific Ocean – then moved west into the Indian Ocean, eventually making landfall in India as – potentially – a very strong cyclone. Of course I must qualify that statement because of the differences in the best track data. The graph at right shows the best estimates of the storm’s intensity, in maximum sustained wind speed. The system gained strength near day 2, then crossed into the Bay of Bengal and regained strength. At landfall in India, it was likely between 70 and 150 knots, kind of a large range. Some of these differences in intensity are due to the data available to each agency. Another could be in the interpretati0n of the imagery.

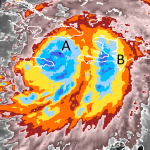

A recent talk post from ibclc2 noted the features in Typhoon Gay during its development in the Gulf of Thailand. The organization of the system is beginning to take shape. The convective cell near B is close to a banding feature (if you were doing a detailed classification). But it is not, since the region between it and the central part of the system is not warm enough (it needs to be red or warmer, see the field guide for more information). The portion near A appears to be an embedded center. But upon further review, there appears a warm spot just north of the darkest blue colors. It could be the beginnings of an eye, but only time will tell … and it does. In the next few images, that small warm spot becomes an eye just prior to making landfall on the Kra Isthmus. So how would you classify it? Well it’s likely best left as an embedded center with no banding. While there is the hint of an eye, the primary characteristics of an eye (cold cloud surrounding a warm center in a circular fashion) aren’t complete yet.

2005 Hurricane Dennis

An image of Dennis recently noted by bretarn showed a large system. Similar to Gay above, the satellite image showed a cold center (A) with a large cold band to the east. The convection near A is showing some circulation, so the center is somewhere below that cold cloud cover. So it is an embedded center. Like the Typhoon above, this is an image just prior to an eye emerging. The next question is what to do with B. It is definitely associated with the system, because it appears to be wrapping around the circulation center near A. The region between A and B is warm, with the warmest color being red. So for a detailed classification, this might be considered a banding feature.

In its own right, Dennis was a very severe system, making landfall in Cuba and in the Gulf on the Florida panhandle. However, its fast movement lessened the impact. It is also less memorable because its Gulf landfall was eclipsed by Hurricane Katrina later in the season. Nonetheless, the name was retired from the North Atlantic hurricane names after the season.

How do I classify this? False eyes

One of the challenging aspects of determining the storm type in Cyclone Center is the inability to view a storm snapshot in context. While classifying a set of images, you do not know which storm you are viewing and how that storm had been evolving before those times shown to you. This can lead to images that can be misleading to classify – one such image is the “false eye” storm.

A false eye is a circular feature of warm cloud that at first glance appears to be a genuine tropical cyclone eye (the center of a powerful tropical cyclone). Since we cannot look at other times during the process to see if the feature persists, we must look for other clues to determine if the feature really is an eye or not. The primary thing to look for is the storm structure outside of the suspicious eye. Does the storm look well organized? Are there distinct and tightly wound spiral bands? Are cloud tops very cold or not so much? Consider the following examples, all examined and discussed in the Cyclone Center Talk feature.

Odette (1985)

The black circle indicates where an eye could possibly be analyzed. But look at the cloud patterns outside of the “eye” for confirmation. Here we see no organized spirals and no circular eyewall (the cold ring the typically surrounds the eye). The clouds are certainly very cold, which is sometimes an indication of strength; but the overall lack of organization leads me to conclude that the “eye” feature is actually just a gap in the cold clouds and not really an eye at all. I would probably classify this as a weak spiral band type pattern, but nothing more.

The black circle indicates where an eye could possibly be analyzed. But look at the cloud patterns outside of the “eye” for confirmation. Here we see no organized spirals and no circular eyewall (the cold ring the typically surrounds the eye). The clouds are certainly very cold, which is sometimes an indication of strength; but the overall lack of organization leads me to conclude that the “eye” feature is actually just a gap in the cold clouds and not really an eye at all. I would probably classify this as a weak spiral band type pattern, but nothing more.

Ami (2003)

The second example is from a very complicated cloud pattern, typically seen in what meteorologists call the “monsoon trough” region. This is an area where the ocean waters are very warm and atmospheric winds tend to come together in the lower atmosphere, creating a situation that is quite favorable for thunderstorms and sometimes tropical cyclones.

The black circle again indicates a circular area of warm clouds that may be mistaken for an eye. What I immediately notice is that there are two distinct areas of thunderstorms, labeled “1” and “2”. Area 1 is showing some signs of organization, shown by the black lines, which indicate a turning or spiraling of the clouds. Little organization is seen in area 2, which is essentially a large blob of thunderstorms at this point. The eye in the middle is actually just a gap in between the 2 systems – there is no organization in clouds around this area.

I classified area 1 as a spiral band pattern. The center of area 1 is probably very close to the circled area (follow the black lines in). Since we are only classifying one system at a time in Cyclone Center, I ignored area 2.

Keith (1997)

To contrast the two examples above, lets look at a real eye. Keith was a very strong tropical cyclone that exhibited a well pronounced eye feature.

At first glance we immediately notice the features of an eye pattern storm: distinct spiral band features, high degree of symmetry, and cold/circular clouds completely surrounding the eye. Although there are even better examples of eye storms, I would classify this image as a mid-level eye pattern. The storm intensity is probably in the Category 2 to Category 3 range on the Saffir-Simpson scale.

I hoped that this helps you to become a better Cyclone Center classifier. Look for more help articles like this on a more regular basis throughout the next few months.

– Chris Hennon is part of the Cyclone Center Science Team and Associate Professor of Atmospheric Sciences at the University of North Carolina at Asheville

When Tropical Cyclones Die

All tropical cyclones die. Sometimes they move over land, sometimes they move over cold water, and sometimes the atmosphere becomes too fierce and rips the storms apart vertically. In this interesting image, highlighted by one of our Cyclone Center collaborators, Tropical Cyclone Davina (1999) appears to have suffered from a combination of these factors. Once a powerful 120 kt. storm, she is now just a pathetic shell of her former self, a swirl of low-level clouds with weak thunderstorms ripped away to her southeast.

Our classifier wasn’t sure how to categorize this storm – what do you think? To learn more, go to Cyclone Center.

– Chris Hennon is part of the Cyclone Center Science Team and Associate Professor of Atmospheric Sciences at the University of North Carolina at Asheville